Poor Boy’s Revenge

“From this valley they say you are leaving,

We shall miss your bright eyes and sweet smile.

For you take with you all of the sunshine,

That has brightened our pathway awhile.”

- Woody Guthrie, Red River Valley

Foreword by Barbara Sessions, Curator

Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum at Falconhead Resort, Burneyville, OK

FOREWORD

The Oklahoma City Thunder’s victory in the NBA basketball finals “is for every Oklahoman who’s ever been underestimated,” read the headline over a guest column in the Oklahoman newspaper on June 23, 2025.

“Along with all overlooked states between the coasts, Oklahoma is the punchline until we’re the headline,” opined Laura Albritten, a writer from Oklahoma who now lives in Colorado.

Agreed, Laura, 100%! I’ve made a study of Waco and Opie Turner for the past 35 years and even created a museum in the Pro Shop to celebrate their significant importance to competitive golf in the United States.

The couple built a challenging course in little Burneyville, Oklahoma, and, counting earlier Pro Tour sponsorships in Ardmore, they put up the money for 19 of the richest and most entertaining professional golf events of the 1950s and 1960’s.

The great men and women pros of the era competed and golf history was made. Players and Tour officials sang the Turners’ praises. But through the decades, (coastal) golf writers tended to ignore the duo or diminish them. Too many have treated Turner’s Lodge as a punchline when it should have been a headline.

Now comes Jared Gallagher to give Mr. and Mrs. Turner the serious attention they have long deserved. Gallagher spent three years doing research then turned loose his exceptional writing talent on this deep dive into a history about which all players and fans can take pride.

The reddirtgolf.com creator has posted several other profiles of course builders, many of them oil millionaires like the Turners. Gallagher humanizes these Oklahoma giants by examining their entire life and motivation. No flyover hit and run piece this. It is the whole truth.

And for all the Oklahoma golfers who wished, just once, they could play a Pro Tour course, there’s only one non-private club to have been an official stop on both the LPGA and PGA Tours. That is the course the Turners built, now a golfing community, complete with hotel and restaurant, known as Falconhead Resort, at Exit 15 (Marietta) of Interstate 35, then 12 miles west on State Highway 32.

Credit: Fonville Studio, courtesy of Turner's Lodge Pro Golf Museum

This valley is known for many things.

Peanut fields and cattle farms. Humble ham sandwiches and empty promises of great riches veiled by the facade of flashing lights and ringing bells. And – most notably - the river that runs red, bisecting the Oklahoma standard from the Texas spectacle.

It was along this valley that a small band of the Wichita tribe ruled following a series of forced removals. From the confluence of the Washita and Red Rivers (now present-day Lake Texoma) to the Wichita Mountains, the Hueco people lived alongside other tribes and an increasing number of white settlers.

Hueco – or “Waco,” in the English language – means “of magic power.”

And on the northern flanks of the Red River Valley, the remnants of one spectacular magic saga remain. It’s a tale of great riches and glory tangled with tragedy and strife. And it has left a legacy that’s almost hard to believe.

Almost.

Drive through the unassuming rock and iron security gate at Falconhead Resort and Country Club in Burneyville, Oklahoma and you might expect that you’re entering one of Oklahoma’s spectacular WPA-era state parks. You’re greeted by a wide four-lane drive divided by a winding streetscape – the kind that were built in those idyllic Post-War, suburban neighborhoods the Cleaver family made so famous in the 50s. As you drive, you’re curious about the eclectic layout of this community – clumps of homes are juxtaposed among massive empty spaces of manicured lawn, wild grasses and native woodlands. If you stray from the main thoroughfare, you’ll get lost in a maze of side streets - many of which are named after Oklahoma towns: Sapulpa Drive, Pawhuska Place and Marietta Circle.

Curious as you may be, you decide its best to stay on Falconhead Drive until you reach a cluster of low-roofed, ranch-style buildings and a parking lot dotted with SUVs and pickups. From above, the centerpiece spreads its wings in every direction: north toward Oklahoma City, south toward Fort Worth, southwest toward Lubbock, northwest toward Denver, southeast toward Dallas and east toward the 18th green.

This structure was once the domain of a boisterous and incollapsible man.

Oklahoma’s only public-play Pro Tour course: Front gate of the 300-home golfing community of Falconhead Resort & Country Club, Burneyville, OK, on July 4, 2025. From 1958-1968, the property was known as Turner’s Lodge, where the golf course hosted a combined six official stops on the LPGA and PGA Tours. This is the only public course in Oklahoma and one of few in the nation to have been visited by both Tours. Eight PGA Sectional Championships also were played on the course (1958-1965), and an Oklahoma Open (1965). (Photo by Barbara W. Sessions)

Waco Turner was slightly built with hawklike vision. His father, a schoolteacher, relocated to Indian Territory from Mississippi in the 1890s. He moved his family to Burneyville, Oklahoma in 1891 to teach at the subscription school there.

Waco followed in his father’s footsteps, teaching at the Hox Bar School after attending higher education at Oklahoma A&M College and Southeastern State Normal School.

He was drafted into the United States Army in May of 1918. The world was suffocated by the first Great War, so Waco packed up and reported for duty at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. The United States needed pilots, but his captain needed a caddie. He would shine shoes and carry the captain’s clubs, who would let him hit a ball every so often. It was here – on the grounds of the Fort Sam Houston Golf Club and A.W. Tillinghast’s Brackenridge Park – that Waco first fell in love with the game. As the war winded down, the great influenza epidemic of 1918 raged. In December, while stationed at Fort Sill in Lawton, he was summoned home on account of the death of one of his brothers. When he made the roughly 110-mile trip home, he found his father and two other brothers gravely ill. This moment may have changed his life forever. Suddenly thrust into the breadwinner’s role for his family, he set his sights toward the new-and-bustling oil industry.

Within a year, Waco transformed himself into an enthusiastic wildcatter with a penchant for gab who bounced around working for various drilling outfits aside from his teaching duties in Overbrook, Oklahoma (seven miles south of Ardmore). Each day before and after classes, he would pass by crews prospecting for black gold. One morning as he ambled by, his nose tipped him off that this particular team had hit the big time. That sweet, yet pungent sulfuric fragrance in the air meant one thing: the students in Overbrook would be without a teacher on that day.

He spent the entire morning, afternoon and night racing around the territory on his horse, gobbling up drilling options. He did the same thing the next day. When he finally took a break, Waco Turner was a rich man.

This discovery near Overbrook sent Turner on a lifetime of chasing the proverbial black golden goose. One of his other early successes was at the Hewitt Oil Field in Wilson, Oklahoma, just east of the prolific “Poor Man’s Field” in Healdton. The two fields, which became indistinguishable throughout the years, were known as such because of the ease of drilling and producing – any “Poor Man” could do it.

By the early 20s, Turner had begun his reign of influence on south-central Oklahoma. He ran for Love County Treasurer and was a member of several fraternal orders and societies, including the Knights of Pythias, the American Legion and the Aahmes Grotto, an order of Masons. According to reports, the “desire of Aahmes Grotto is to bring together in the spirit of sympathy the entire Masonic body of southern Oklahoma to get acquainted and cultivate a friendly relation that ought to exist between all men who have taken the same solemn vows, and to build lasting friendships as a monument to endure forever.”

Scrolls of Aahmes Grotto included Robert A. Hefner (Ardmore mayor and attorney to oil and gas giants), Samuel Lloyd Noble (oilman and philanthropist) and Perry Duke Maxwell (banker and soon-to-be world-renowned golf course architect).

Throughout the 1920s, Waco Turner worked his way through the Poor Man’s Field and others like it. He was a risk-taker, gambling on each lease he could acquire. He had built a nice life for him and his new wife, Opie, but that came crashing down when the Depression hit.

When he was tipped off about prospects in East Texas, he couldn’t convince any bank in the area to loan him money. That could be where his distaste of banks – and bankers – was derived. Legend goes that one banker wouldn’t loan Turner $500 to get up and running in East Texas. Years later, after many successes, Turner returned to Ardmore and bought the bank just so he could fire the man who wouldn’t offer him the loan.

Within a matter of months, Waco and Opie were erecting their oil empire. They had just built a home at 1501 3rd Avenue SW in Ardmore, but by 1932 were splitting their time between Ardmore and the East Texas oil fields. When he was in town, he could be found at Dornick Hills Country Club, Perry Maxwell’s home course and first design, where he held a membership. He was an average golfer, shooting anywhere from 80-95, but was passionate about the game. In February of 1934, he was first elected to the board of directors of the club. Maxwell was unanimously reelected as the club’s secretary.

In early April of 1935, as Gene Sarazen hit the “shot heard ‘round the world” to win the Augusta National Invitation Tournament, Turner was camped out beside the No. 1 Munson, a deep test well he was drilling in Fox, Oklahoma, nearly within earshot of the original Poor Man’s Field. By the beginning of May, he had drilled to a depth of 3,400 feet. With no payoff yet, Waco claimed he would drill to 6,000 feet to find a payoff if he needed to. By October 1, Waco’s deep test had hit a standstill at 5,025 feet. He decided to rack his drilling tools and wait for new prospects to come. That same day, he took a private plane to Tulsa, then to Detroit where he attended the 1935 World Series between the Tigers and the Cubs.

Turner, always the avid sportsman and spurred on by his trip to the World Series, bought a baseball franchise in Ardmore as part of the Oklahoma State league in the spring of 1936.

By 1937, Waco had become the president at Dornick Hills. That was short-lived, however, as he soon moved his operations to Alice, Texas. For the next several years, Turner served off-and-on in various capacities of the board.

In 1944, clubs around the United States were shuttering. Several Perry Maxwell designs in Tulsa closed their doors during wartime, never to reopen. In August of that year, the Dornick Hills clubhouse suffered a devastating fire as it was being used by officers of the Ardmore Army Air Field. The clubhouse was a total loss, as was the furniture, equipment, golf clubs and other belongings housed in the locker rooms. Nineteen-year-old Bobby Lively perished in the early-morning blaze, his charred body found in the wreckage after the sun arose.

The fire devastated the club’s membership, but they were determined to build back. By the summer of 1945, with Turner back at the helm, the newly reorganized and rechartered club announced the construction of a new fireproof clubhouse at the cost of $55,000.

The new clubhouse opened in April of 1947 and the following summer the club hosted the inaugural Dornick Hills Invitational. Ardmore native Charlie Coe – fresh off victories at the Trans-Miss and Broadmoor – needed just 29 holes to dispatch Warren Higgins, 8 and 7, for the victory. Coe would become one of the most decorated amateur golfers in history, amassing two U.S. Amateur titles, four Trans-Miss titles, one Western Amateur title and setting records at The Masters for most cuts made as an amateur (15), top-25 finishes as an amateur (9), top-10 finishes as an amateur and most times as Low Amateur (6). He also holds the record for best finish as an amateur (solo 2nd in 1961) and the only person to earn Low Amateur honors in four different decades.

The new clubhouse and Dornick Hills opened in April of 1947.

It was after the war that Waco stumbled upon his third (and final) fortune. In the hills south of Velma, he smelled potential. Convincing Opie to move out of their home in Ardmore, they set up a tent and lived in the field for two years. By 1950, he had amassed a fortune that was estimated between $40-50 million (or 40 to 50 “barrels” as he called it) with assets including 80 producing wells, an 800-acre ranch in Burneyville, a fleet of 10 private automobiles, a yacht on Lake Murray and a house in Miami, Florida (also with a yacht).

It was also at this time that his sporting passions were catching up to him. Waco and Opie spent their winters in Miami, but traveled the United States to watch the world’s best tee it up. From Pinehurst to Palm Beach to Augusta, they traveled the professional golf circuit. It was here that he decided that he wanted to bring a professional golf tournament to Dornick Hills.

Waco got that opportunity in 1952, when – as club president once again – he persuaded PGA Tour officials with the largest potential winner’s pot of the season: $15,000. It wasn’t just that – he also bankrolled a $40,000 pro shop, hired legendary golf professional Dutch Harrison to manage the club and bought up every hotel room in Ardmore and at the Lake Murray Lodge for players and Tour officials. When Oklahoma Governor Johnston Murray was denied a room at the lodge for his summer vacation, Waco offered up his yacht – as long as the Murrays wore only new, white tennis shoes on board.

First-Tee Sight - Golfer teeing off on number one at Ardmore's Dornick Hills has this view of new $40,000 pro shop which Waco Turners donated to club. All furniture in pro shop is made of Philippine mahogany, was built in Ardmore. Date Created: 1952-07-21 | Courtesy of Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas, Arlington

Assistant Pro Fred Knight stands by "Lazy Susan" putter rack, feature of the new $40,000 pro shop which Millonaire Waco Turner built at Dornick Hills Country Club, Ardmore, Oklahoma. Date Created: 1952-07-21 | Courtesy of Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas, Arlington

In all, Waco spent more than $120,000 out of his own pocket to get the club and Ardmore ready for the world’s greatest golfers. The first Ardmore Open was won by Dave Douglas, a lanky Delaware man who finished the tournament at -1 and took home the $2,400 first prize. Dutch Harrison placed second and Lloyd Mangrum, third. The low amateur for the event was Oklahoma A&M standout George Bigham, who finished in 11th place – tied with George Fazio.

While the prize money topped the Tour’s list for 1952, it was dwarfed by Waco and Opie’s “pay-for-play” system. Handing out cash bonuses for birdies, eagles, low rounds of the day and so on, they doled out nearly $24,000 to the field. Douglas’ $2,400 was tops on the Tour, but Opie threw in an additional $3,000 for winning the event. Thus began an under-the-table tradition that had pros clamoring to travel to Ardmore, Oklahoma in the heat of the summer. In a season recap, Horton Smith claimed that the ’52 Ardmore Open was one of the three most talked about tournaments of the year.

While the ’52 event was considered by most a smashing success, the club’s benefactor, Perry Maxwell, wasn’t able to experience it. Bedridden by cancer, the world renowned golf course architect would pass away in his Tulsa home in November of that year.

The 1953 tournament was scheduled to be a month earlier, in May. In an effort to grow the event, Waco invited Bob Hope, Phil Harris and Bing Crosby as celebrities. They also announced an increase in both prize money and bonus money. They even offered $100 to the unlucky competitor who records the highest score on the Cliff Hole. Had they offered that in the inaugural event, Bill Jelliffe would’ve taken the prize – he took 19 strokes to complete the hole.

In fact, the bonus money in ’53 dwarfed the year prior. The rundown was as follows:

Waco and Opie loved to up the ante. Halfway through the tournament, they announced that they were increasing the prize money by $5,000. Earl Stewart, Jr. won the tournament, cashing a check for $6,900. In all, Turner doled out nearly $15,000 in bonuses.

The third annual Ardmore Open brought even more prize money, as Julius Boros took top honors and was presented a check for $7,200 - $100 for every hole of competition.

The spring golf fest was such a success that the Turners decided to host a ladies professional event in the fall. The first event featured all the top women, including Betsy Rawls, Patty Berg and Babe Zaharias. The Turner’s gave Babe a horse, but Berg took the top prize of almost $2,000.

Babe Zaharias Rides ‘Superman’: At the close of the 1954 Ardmore Open, the sponsors, Waco and Opie Turner, presented a gift palomino to LPGA President Mildred “Babe” Zaharias for bringing the LPGA to visit Oklahoma for the first time. It was the richest event ever played by the LPGA Tour, which started in 1950. Zaharias stayed overnight that week at Turner’s Lodge, where guest cabins had just been finished for the future Turner’s Lodge course. The great Olympian and golfer, voted by AP as the most outstanding female athlete of the 20th century, kept the horse there and was a frequent visitor to Burneyville until her untimely death, of cancer, in 1956. (Fonville Studio photo, courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

Waco ran his tournaments the way he ran his business – with complete autonomy. This ultimately rubbed the Dornick Hills board of directors the wrong way. When they approached him about giving up some of his control of the event, he felt betrayed. After all, it was he who had brought the PGA and the LPGA to Ardmore, Oklahoma in the first place. According to Tulsa World sportswriter Tom Lobaugh, Turner was “piqued by criticism and lack of cooperation” from the rest of the board of directors. In a brash decision, he relinquished his role as club president and gave up his membership, promising to build his own golf course. He told the membership at Dornick Hills when he brought the Tour’s best back to Oklahoma, they would never step foot in Ardmore again.

Thus began Waco’s quest to build his own paradise. On the ranch his father once owned near Burneyville, he planned a million-dollar dream course, complete with lakes, lodges, guest cabins, an airstrip, a swimming pool and more. Using his own imagination to design the course and his oilfield roughnecks to construct it, he promised to pattern the holes after some of the most famous in the world. Drawing from his experiences playing Augusta National, Pebble Beach, Pine Valley and Oakmont, the course was planned to be a par 72 just over 7,000 yards with prominent water and doglegs as defense on the hilly layout.

On a visit to the course during construction, Dutch Harrison claimed it would be one of the toughest courses in the nation. Before the track was completed, Waco announced that it would be ready to host a PGA event by 1958, and he planned to make it a $100,000 event.

By the end of 1957, the price tag on the Turner Lodge approached $2 million. If the duo was worried about hemorrhaging money on the project, they hid it well. They hosted several events at the lodge as the golf course was maturing, and announced that the LPGA would return to Oklahoma in 1958 for the inaugural Opie Turner Open.

LPGA Tour Officially Opens Turner’s Lodge: Mickey Wright, still considered by golf historians as the greatest female golfer of all time, is congratulated by her hostess after winning the Opie Turner Open in Burneyville, OK, on September 3, 1958. What other golf course in history has opened with a Pro Tour stop? (Photo in the Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum, courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society)

Mickey Wright won that Labor Day tournament, and the legend of “Golf the Turner Way” grew evermore. It wasn’t because of the reverence or respect the Turners had for the traditions of professional golf.

No.

Instead, they took the traditional golf tournament and flipped it on its head. Like a precursor to LIV’s motto of “Golf, But Louder,” the Turners treated their golf tournaments like carnivals. Trick ropers, comedians, live music and more dotted the fairways of the Turners’ tournaments. It would be nothing to hear shotgun blasts in the distance or feel the whir of a crop-duster crop-dusting your approach shot, or see Waco barrel a brand-new Cadillac across a green. The free-flowing cash prizes, nightly poker games in the dormitory-style cabins and fishing for monster mudcats on the banks of Lake Turner were just icing on the cake.

Cadillacs to Spare: Chris Gers, future club pro at Turner’s Lodge, Duffy Martin, owner of Brookside Golf and later to build Guthrie’s Cedar Valley and Cimarron National courses, and his brother Jack Martin load their clubs in 1958 into the trunk of a 1955 Cadillac Waco Turner gave to Duffy Martin. “My car broke down when I was at Turner’s Lodge. Waco Turner had lots of Cadillacs. He pointed to one that was parked in the weeds. He said the car needs a battery and if I got the car running, I could have it. I hitched a ride to Marietta to buy a battery and left Turner’s Lodge in style,” Martin said. For his outstanding career as a player and golf course builder, Martin will be inducted posthumously in the Oklahoma Golf Hall of Fame in 2025. (George Tapscott photo inTurner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum, courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society)

When Waco convinced the PGA Tour to return, it did so with a caveat. The event was to be held the same week as the Tournament of Champions in Las Vegas. That meant that the Tour’s top members would never step foot on Turner’s golf course. But that was just fine with him. He didn’t host the event to rub shoulders with Byron Nelson or Ben Hogan – he already knew them. He did it for his pure, unadulterated love of the game. Thus began the unofficial moniker of the “Poor Boy Open.”

The times were high for the Turners, but friends and acquaintances grew concerned for the couple – both for their finances and their well-being. Waco, ever-wary of the banking and financial system as a whole, never invested his wealth. The tax rate for the uber-wealthy was astronomical – up to 85%. It is estimated that he spent close to $30 million of his own money on bankrolling his tournaments.

Silver Service at the 1959 Opie Turner Open: Waco and Opie Turner were assisted by Miss America 1958 Mary Ann Mobley (right) in presenting the low amateur prize to Jean Ashley of Kansas, in the 1959 Opie Turner Open at Turner’s Lodge. Ashley had to go two extra holes with Oklahoman Susie Maxwell (Berning), age 18, for the win. Maxwell-Berning turned pro in 1964. She went on to win the U.S. Women’s Open three times and was a multi-winner on the LPGA Tour before being inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2022, with Tiger Woods. (Fonville Studio photo, courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

The other issue was his penchant for the bottle. Always up early, Waco insisted on a mid-afternoon siesta, one that usually included a “jug of bourbon.” Opie was also drowning in the drink. One evening in late August 1962, Waco was in the golf shop attending to end-of-day business. He instructed an employee to walk a note to his house, letting Opie know he’d be home soon. The employee walked in and found a drunk Opie stumbling about the home, bleeding from two holes in her side. They were .38-caliber gunshot wounds, and they were later ruled to be self-inflicted. Opie was rushed to the hospital, and for a few days it seemed she would recover. But a bout with pneumonia took hold and never let go. Opie died at the age of 61.

Waco never quite recovered from Opie’s passing. The tournament lasted a few more years, but when the PGA threatened to make the event’s status unofficial, he reportedly wrote back, “If my tournament is so insignificant, then it should be called off.” The 1964 Waco Turner Open was the last to be played. That year, an affable young Black man from Jackson, Mississippi was in the field. His first official year on the PGA Tour (even though Blacks were only allowed to play in half of the full field events), Pete Brown showed up to Burneyville with a smile and his friend, Charlie Sifford, in tow. Brown found favor with Turner and his track, and led by one heading to the 72nd hole, a daunting and dead straight 232-yard uphill par three. Adrenaline surging, Brown blasted his tee shot beyond the green, the ball resting in a loose pile of rocks. If nerves were getting to him, he didn’t show it, as his chip off the rocks came to rest two and a half feet from the hole. He would sink the putt, earning more than $3,000 and shattering barriers as the first Black man to win an official PGA Tour sanctioned event.

Historic First Win on Tour by a Black Golfer: Waco Turner presents the winner’s check to Pete Brown, the first African-American member of the PGA to win an official PGA Tour event. Falconhead Resort and Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum hosted the late Pete Brown’s family, golf dignitaries, historians and the public to the 60th anniversary celebration of that historic win on May 1, 2024. (Ron Cross photo courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

The victory earned Brown an invitation to the following week’s Colonial Invitational in Fort Worth, where he would become the first Black man on the tournament’s history to compete. Brown was admittedly “scared to death,” and Waco would ease his nerves by escorting the golfer on the grounds with a pair of pistols on his hips. Sixty days following Brown’s victory in Burneyville, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, 101 years earlier. Brown wouldn’t win again until 1970 at the Andy Williams-San Diego Open. It would be his last victory on Tour.

Many oilmen have created generational legacies in the game of golf in Oklahoma. Waite Phillips and Southern Hills. His brother Frank and Hillcrest. Turner sold his interest in Turner Lodge in the late 60s and never revisited the game. He would die in 1971 from a longstanding illness. That same year Robert Trent Jones redesigned the course and it was renamed Falconhead Resort Country Club. The only thing of significance that remains in the oilman’s name is Turner High School, which is located about 900 yards off the golf course property. Of the 11 state championships in the school’s history, seven have come from golf. The Lady Falcon’s most recently finished 2nd in the 2025 Class 2A state championship, ending a run of four consecutive state titles.

Historic 18th Green at Turner’s Lodge: Pete Brown sank a must-make one-putt for par to secure a one stroke victory over Dan Sikes in the 1964 Waco Turner Open and make history as the first African-American member of the PGA Tour to win an official event. The original hole played as an uphill, 232-yard par 3. In this 1971 photo architect Robert Trent Jones has added the island tee to extend the hole to a 287-yard par 4. (Photo courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

Impeccable Bent Grass Greens: Falconhead Course Superintendent Edward McKinney’s bent grass greens rival the best in Oklahoma. Seen is the #10 green and in the background, the #15 green on July 4, 2025. (Photo by Barbara W. Sessions)

Today, Turner's Lodge, the Turner residence and other original cabins, and the Pro Tour course that the generous couple built still stand, full of life and tribute to the founders and to the hundreds of pro players who walked these fairways. The Turner's Lodge Pro Golf Museum, open daily in the pro shop at Falconhead Resort, tells the stories of the 19 professional tournaments underwritten by Waco and Opie Turner at Dornick Hills (1952-1954) and Turner's Lodge (1958-1965). Those include three visits by the LPGA Tour and seven PGA Tour stops, as well as eight consecutive South Central PGA Championships and an Oklahoma Open. Thanks to the Turners, Falconhead Resort is the only public-play course in Oklahoma and one of a handful in the nation, to have hosted official events of both the men's and women's golf tours.

In 2024 Falconhead held a national celebration on the 60th anniversary of Pete Brown's historic victory as the first African American to win on the PGA Tour (the 1964 Waco Turner Open). Noted golf authors, historians, friends and former players in the Pete Brown era, spoke from the 18th green and then held a historic replaying of the 18th hole, using Waco Turner's golf clubs.

Writers and golf leaders of the 1960s recognized the tremendous boost to professional golf brought by the Turners' imagination, wit, generosity, and quality presentations. Bud Shrake, golf columnist, wrote in Sports Illustrated in 1964, "This course (Turner's Lodge) is good enough, tough enough, and interesting enough to be a championship one." Thomas Crane was PGA Executive from 1944-1964, long enough to have witnessed all the events the Turners put on in Ardmore and Burnevyille. Crane said, while attending the 1963 Waco Turner Open, "I personally feel that Waco Turner has done more for professional golf than any man I've ever known." Marilynn Smith, an LPGA co-founder, was president of the LPGA when that Tour held its annual meetings at the Opie Turner Open in 1958 and 1959. She later wrote a book about the Tour's first 10 years (1950-1959) saying of the Turners, who sponsored three LPGA tournaments in that decade, all paying top prize money and bonuses, "We couldn't have done it without them."

Turner was a living symbol of maverick generosity: a ruggedly independent soul who returned countless dollars and opportunities to the “also-rans” of the pro golf world because he believed in making sure everyone got a shot. Whether he was blasting turtles with his .410 shotgun, rolling out potato-sack bonuses in cash or cheekily co-opting a Cadillac as a 19th-hole shuttle, his life was a grand gesture against the polished pretenses of the golfing elite.

Turner didn’t chase headlines or alliances. His conviction was equal parts savvy and showmanship, played out on a stage populated by ducks, bullfrogs and oilfield roughnecks -Turner’s own crowd. And in doing so, he made room for the underdogs and the overlooked: for them, and perhaps more importantly, for all of us who’ve ever felt like the “Poor Boy.”

“So come sit by my side if you love me.

Do not hasten to bid me adieu.

Just remember the Red River Valley

And the cowboy that has loved you so true.”

- Woody Guthrie, Red River Valley

The Turner Bonus Plan – Cash for birdies, eagles, chip-ins, and other exceptional scores, was a generous innovation of the couple (seated here behind envelopes of cash). The Turners paid out almost as much in bonuses to all players as in prize money to the top finishers. (Fonville Studio photo, courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

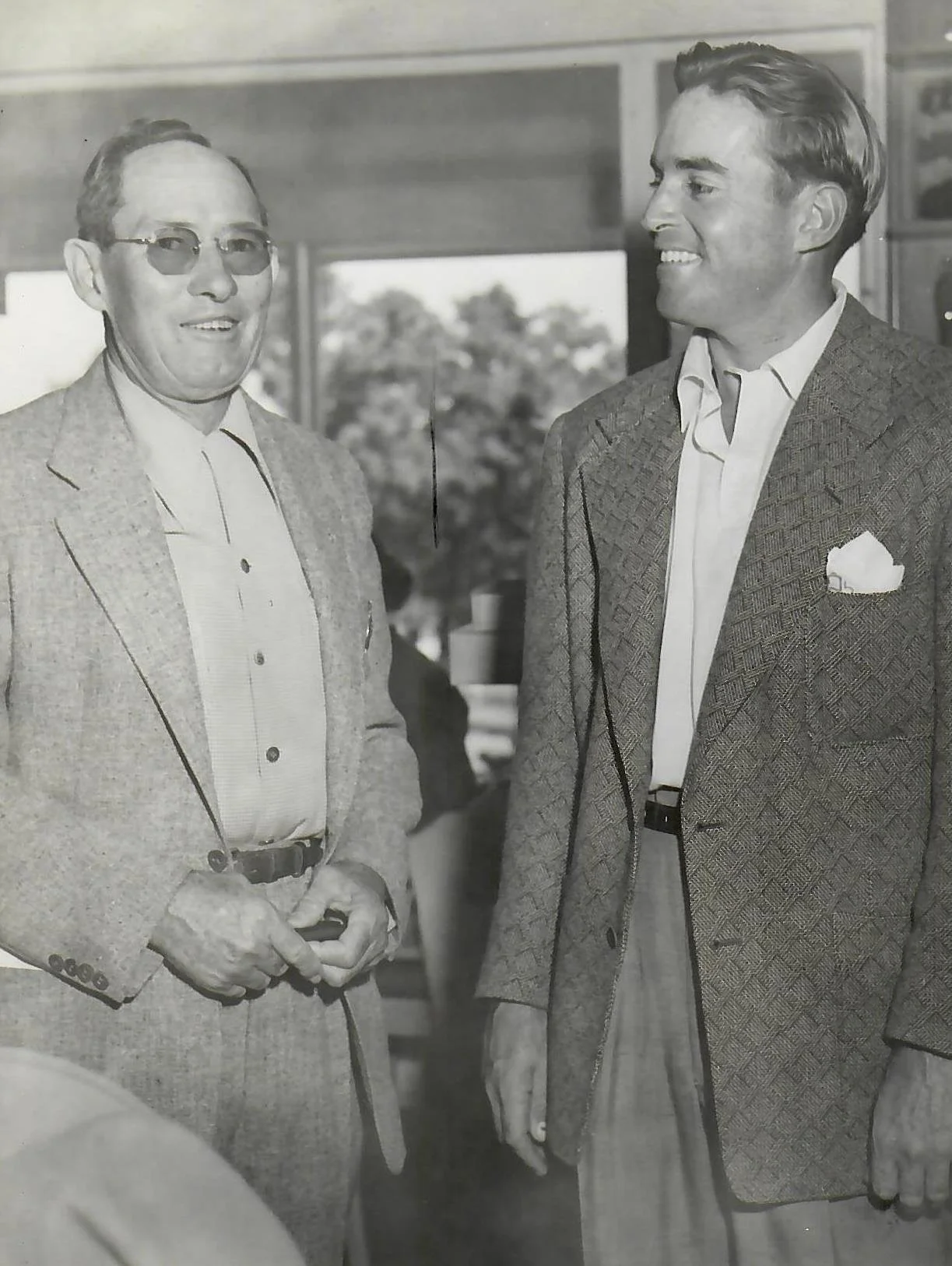

Most Competitive Waco Turner Open: Johnny Pott had to shoot a tournament record 276 (16 under par) to hold off rookie Jack Nicklaus (right) and others in the 1962 Waco Turner Open in Burneyville, OK. (Photo courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

A Turner Favorite, Bo Wininger, in 1962: The Commerce native and Oklahoma State University golfer won seven times on the PGA Tour in the 1950s and1960s. He finished in the money in the Waco Turner Opens and twice won the South Central PGA Sectional Championship at Turner’s Lodge. Wininger was inducted in the Oklahoma Golf Hall of Fame in 2023. (Fonville Studio photo, courtesy of Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

1964 Waco Turner Open: Dale Douglass, born in Wewoka, was a 28-year-old assistant pro in Denver when he posted a one-under par 36-35 - 71 in the opening round of the 1964 Waco Turner Open at Turner’s Lodge in Burneyville. Douglass compiled a record of three wins on the PGA Tour and 11 wins on the Senior (Champions) Tour. (Photo in Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum, courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society)

Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum in the Pro Shop at Falconhead Resort, Burneyville, OK: The first official win by a Black golfer happened at Turner’s Lodge in the 1964 Waco Turner Open. The museum sponsored the Pete Brown Diamond Jubilee in 2024 on the 60th anniversary of his historic win. (Display in the Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

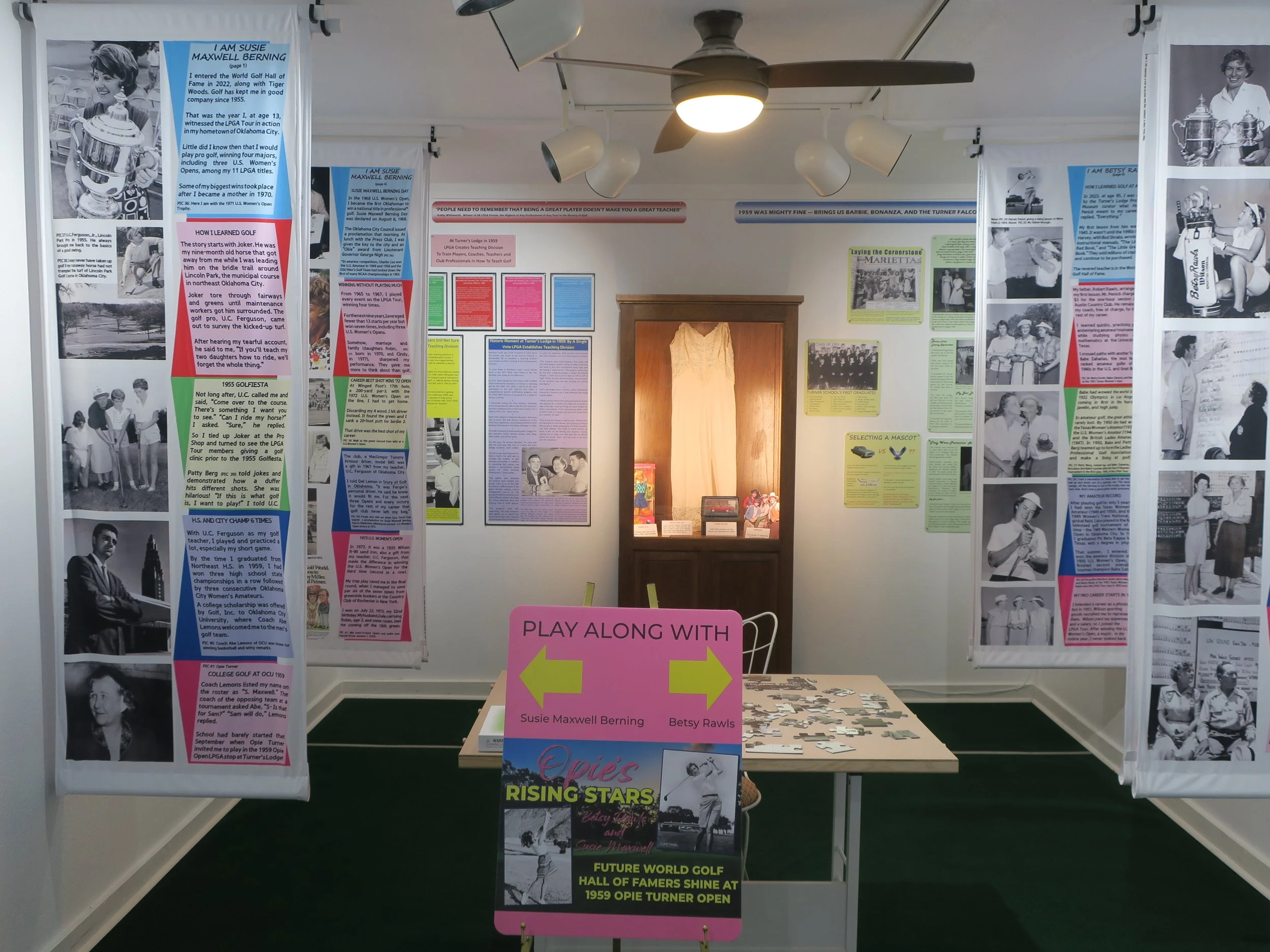

Opie’s Rising Stars Features Susie Maxwell Berning and Betsy Rawls: The two LPGA stars finished their careers in the World Golf Hall of Fame. Both won three U.S. Women’s Opens. Their paths crossed for 10 years in LPGA Tour stops in Oklahoma. They competed first in the 1959 Opie Turner Open, when Berning was an Oklahoma City amateur and Rawls a young LPGA winner, including the Opie. By 1964 Berning had turned pro and she beat both Rawls and Mickey Wright for her first LPGA Tour win, in 1965, in Oklahoma, at the Muskogee Civitan Open. (Display in the Turner’s Lodge Pro Golf Museum)

POSTSCRIPT

In all, Waco and Opie Turner hosted 19 professional events in their lifetimes.

Ardmore Open (PGA event at Dornick Hills Country Club)

1952 –Dave Douglas

1953 – Earl Stewart

1954 – Julius Boros

Ardmore Open (LPGA event at Dornick Hills Country Club)

1954 – Patty Berg

Opie Turner Open (LPGA event at Turner’s Lodge)

1958 – Mickey Wright

1959 – Betsy Rawls

Waco Turner Open (PGA event at Turner’s Lodge)

1961 – Butch Baird

1962 – Johnny Pott

1963 – Gary Brewer, Jr.

1964 – Pete Brown

Oklahoma Open

1965 – Buster Cupit

South Central PGA Sectional Championship

1958 – Ted Gwin

1959 – Buster Cupit

1960 – Buster Cupit

1961 – Pete Fleming

1962 – Francis “Bo” Wininger

1963 – Francis “Bo” Wininger

1964 – Chris Gers

1965 – Ted Gwin

In all, the Turners handed out $343,638 in prize money.